Over the years Graphisme en France evolved, adding more editorial content to the calendar. When Véronique Marrier joined the Centre national des arts plastiques in 2004, serving first as a collaborator, then as Emanuel’s successor in 2008, and now as head of CNAP’s graphic design collection, the publication gradually developed into its current form: an annual thematic magazine, which in 2014, on the twentieth anniversary, had its first English edition.

Each year Marrier chooses a subject related to the contemporary debate around graphic design: tools, graphic design and society, graphic design and writing, typography, exhibitions, visual identities, and research are some of the themes covered in recent years. Around these topics practitioners, researchers, and critics – from France and abroad – are invited to contribute to the development of the discourse.

The latest issue of Graphisme en France, Histoire(s) de design graphique, no. 29, centers around graphic design history and builds on a discussion that has been going on in the last 30 years about how graphic design histories have been produced and presented. It developed out of a conversation between Alice Twemlow, design historian and critic, and Sara De Bondt and Catherine Guiral, two graphic designers whose work often intertwines with historical research. This dialogue somehow echoes the one that took place in 1992 between Robin Kinross and Richard Hollis in the way it freely discusses several problems related to researching and writing the history of graphic design.1

Cover of Histoire(s) de design graphique, designed by Juliette Flécheux, 2023.

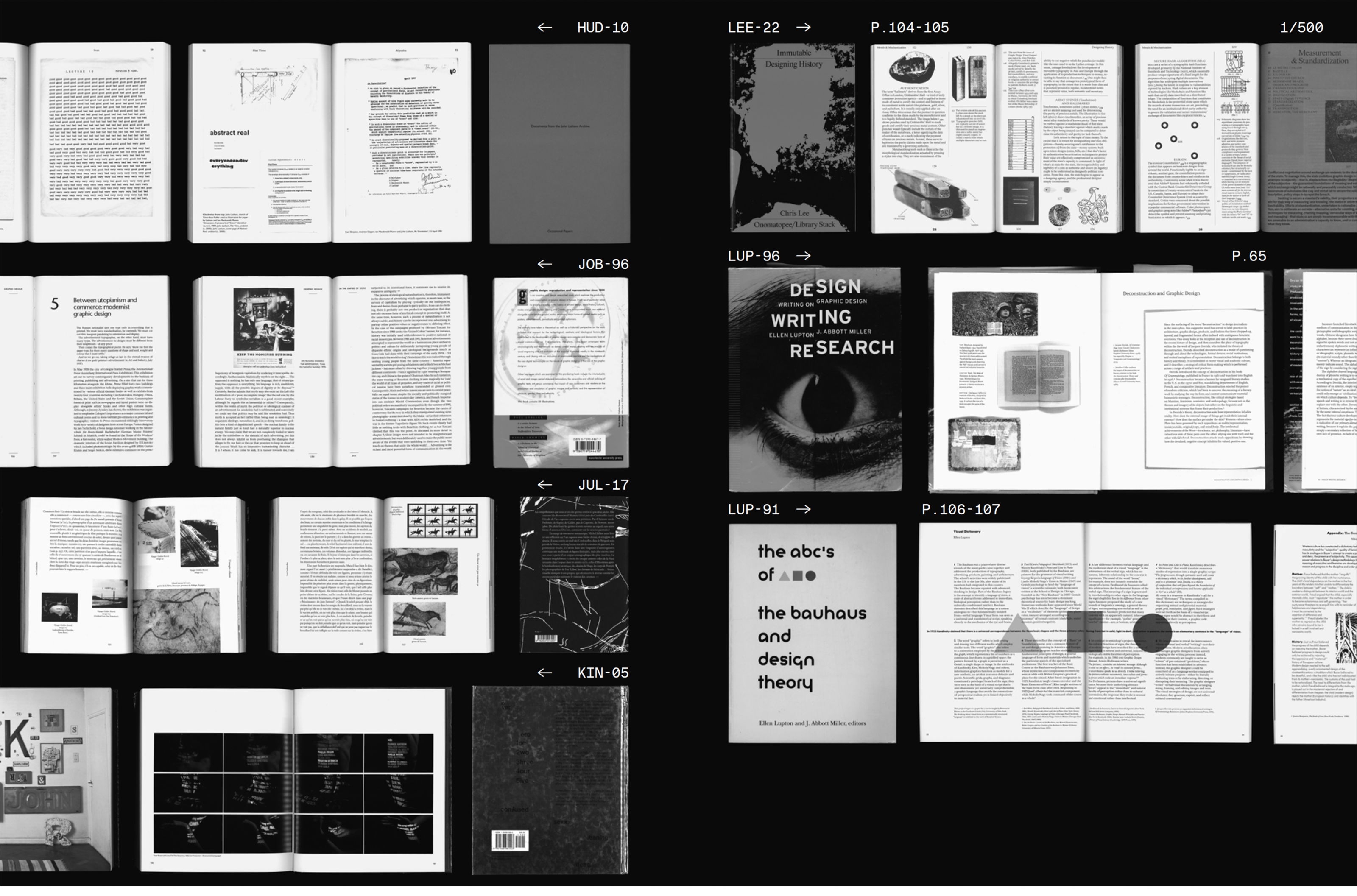

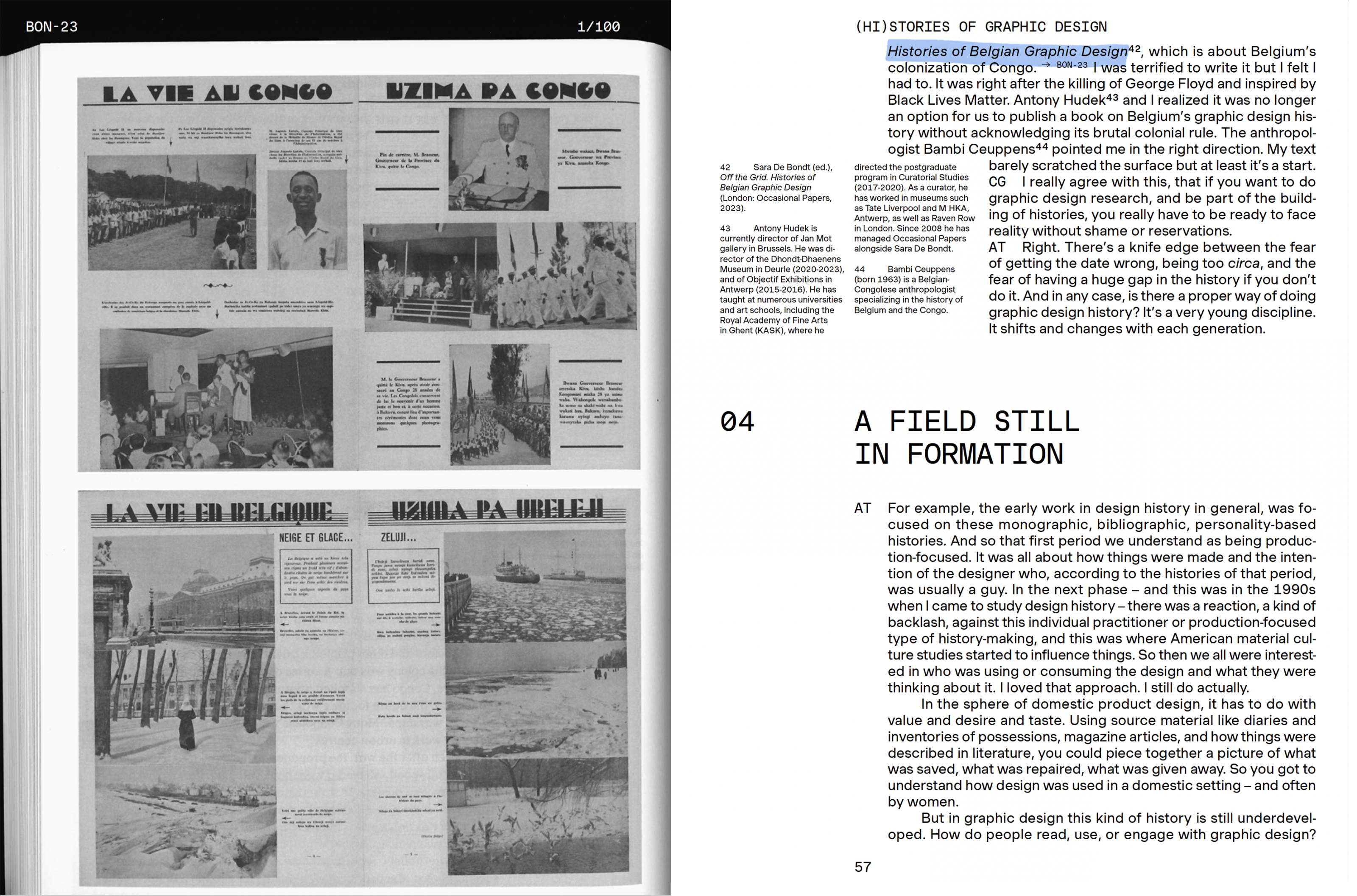

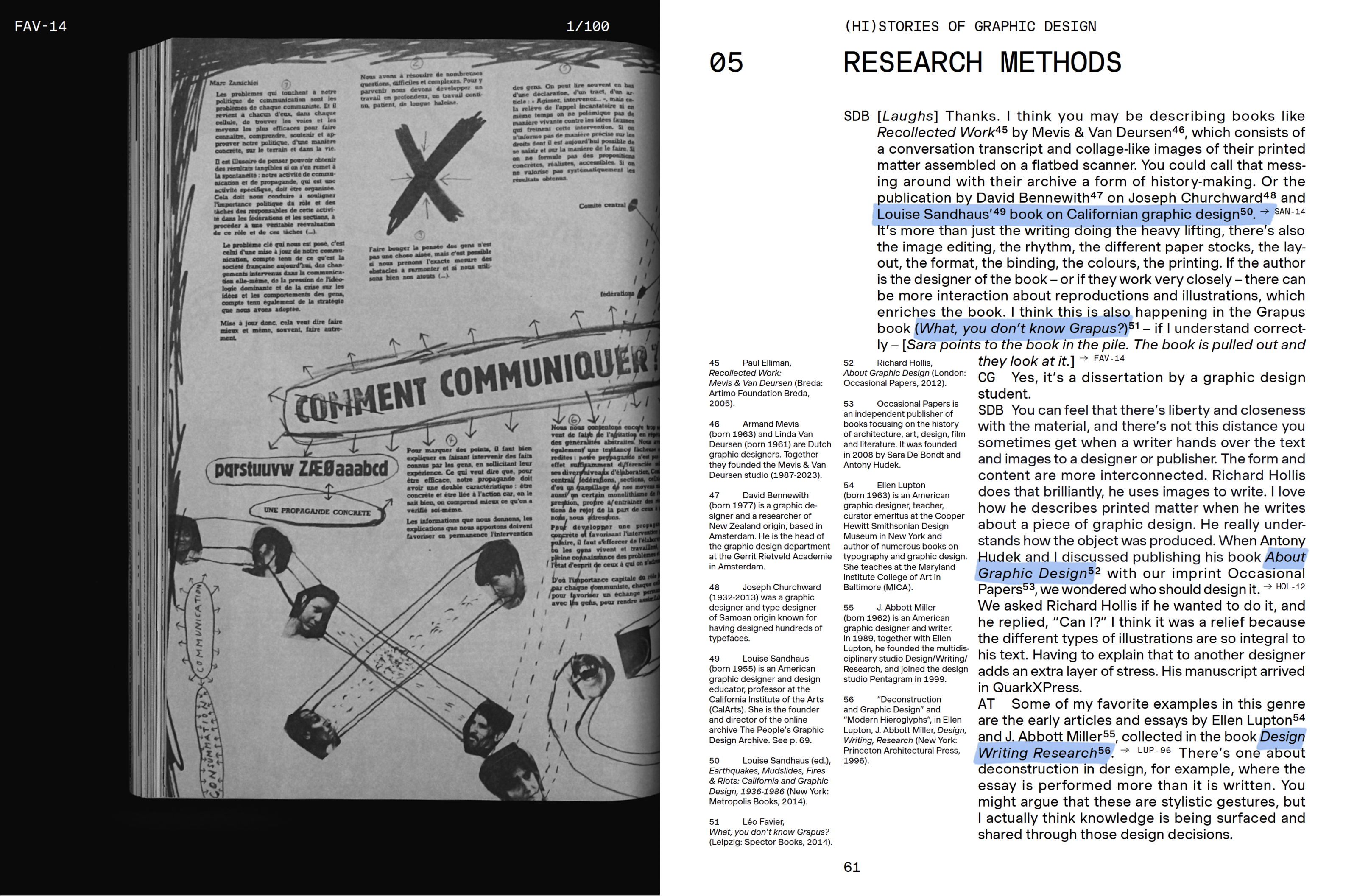

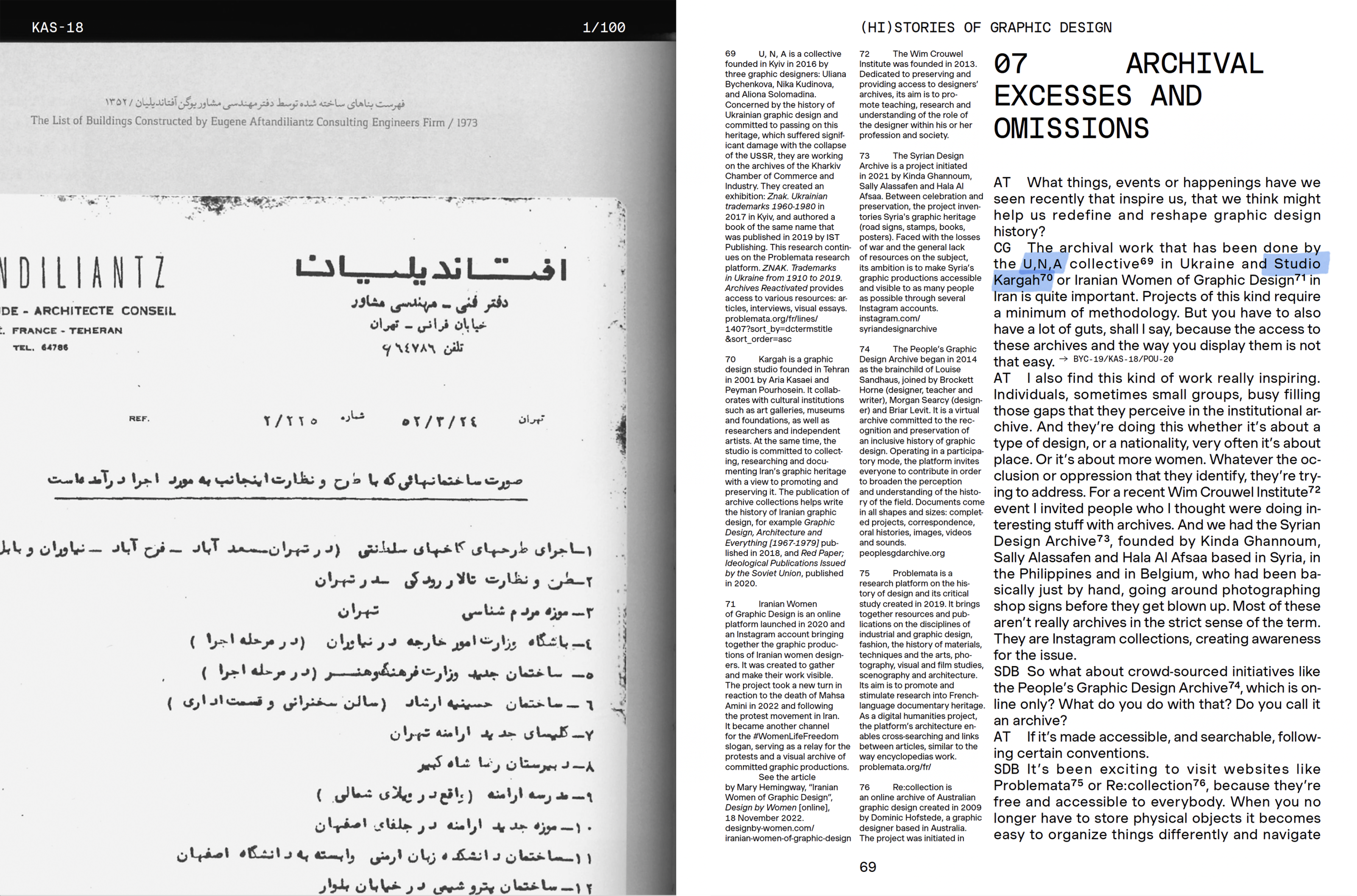

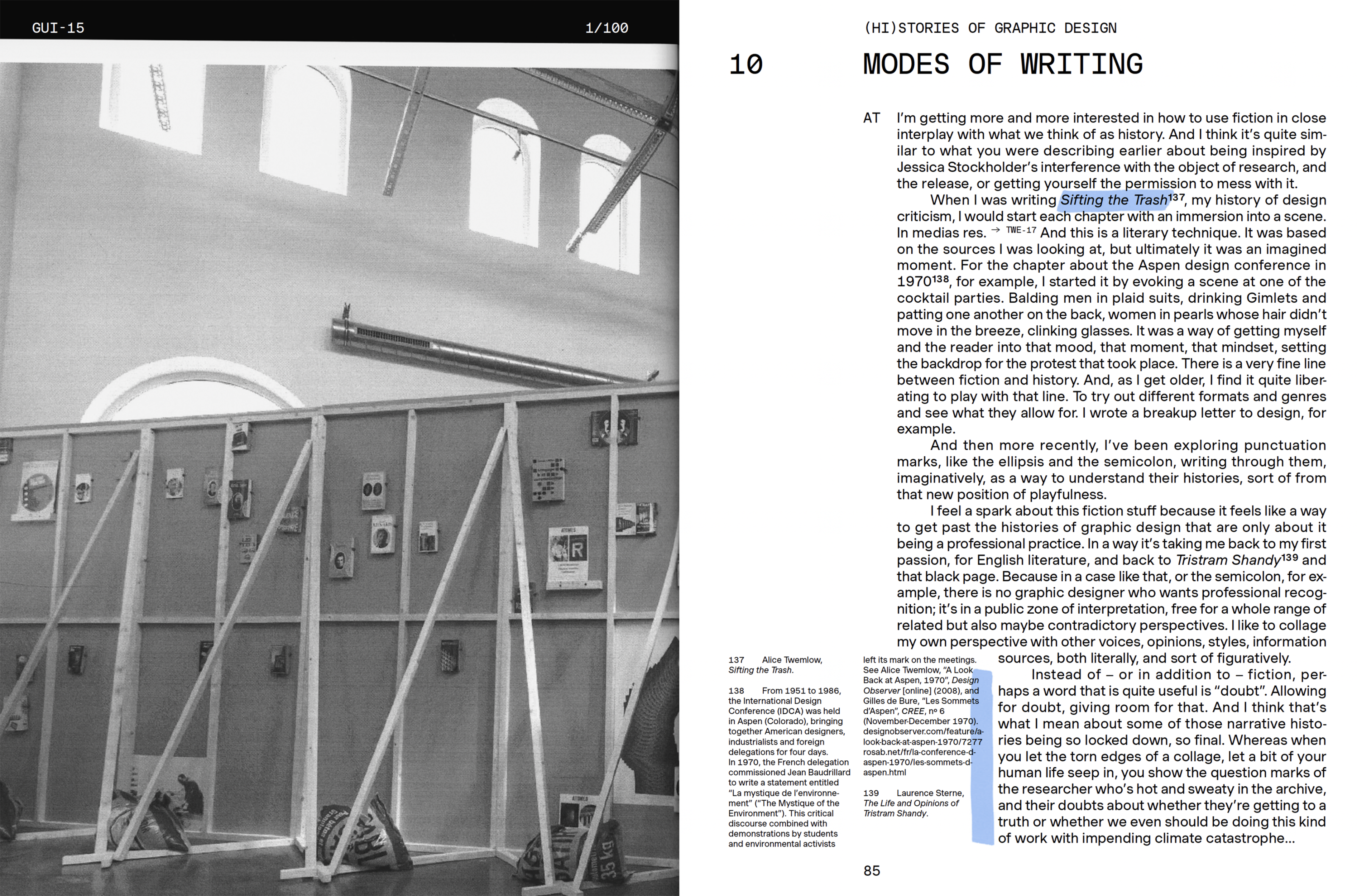

Many of the existing books on the subject, providing context to the conversation, were physically laid out on a table at the meeting and are presented in this publication, carefully designed by Juliette Flécheux, over several pages of scanned spreads that are referenced throughout the dialogue. These books include classic history manuals such as Richard Hollis’s Graphic design. A concise history from 1994, historiographic surveys like Sara De Bondt and Catherine de Smet’s Graphic Design: History in the Writing (1983–2011) from 2012, and recent attempts at revising the canon such as Briar Levit’s Baseline Shift, Untold stories of Women in Graphic Design History, 2021. The designers of the books are always mentioned in the reference list as a way to close the gap between researching, writing, and designing in the historical field.

The different background of the three invitees provides an interesting starting point for the discussion: each begins by explaining how they got in touch with graphic design history, first as students, then as practitioners. By situating themselves as active agents in the field, De Bondt, Guiral, and Twemlow avoid abstract statements and always connect to the real experience of doing historical research and trying to make sense out of it.

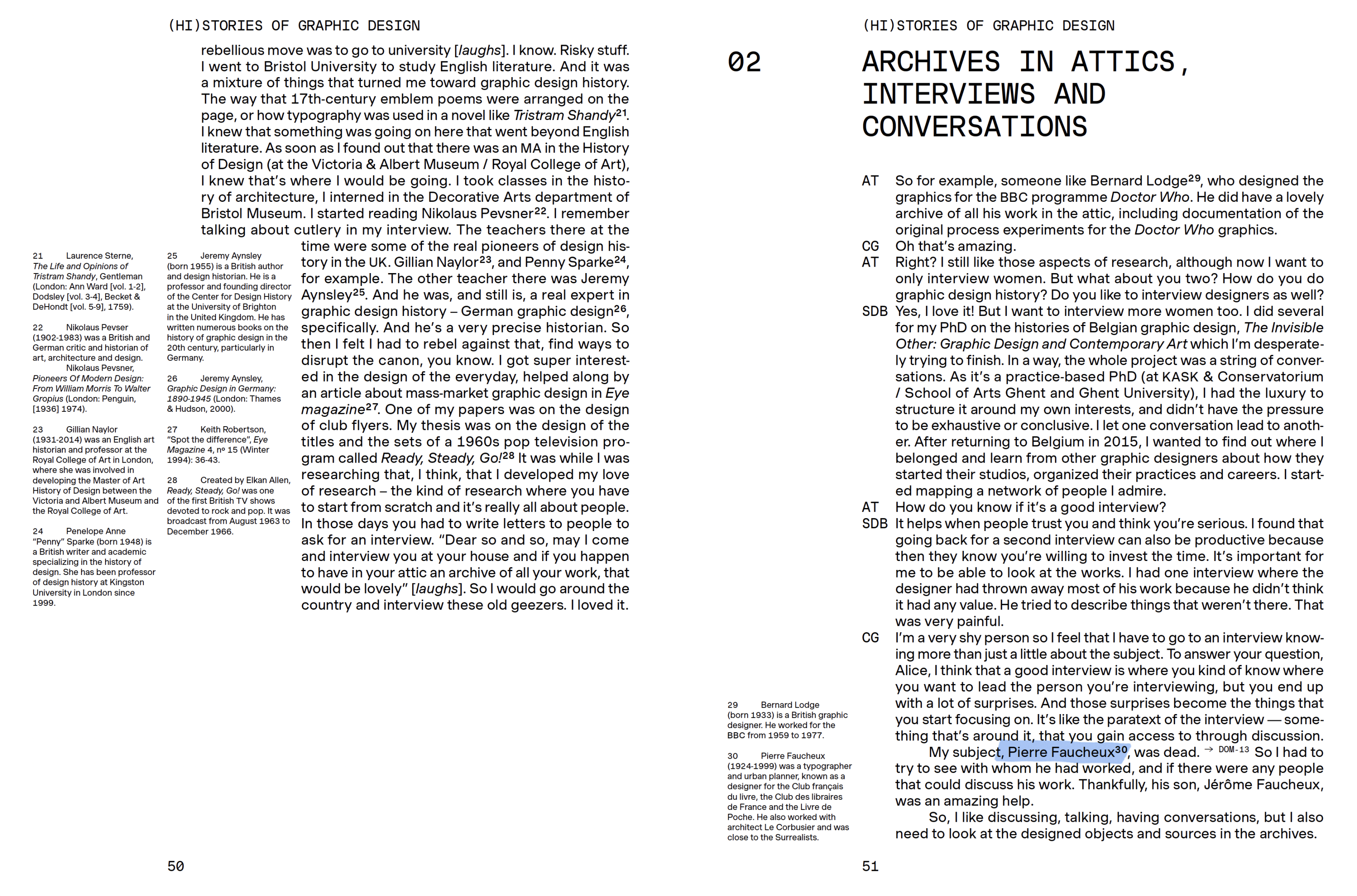

Interviews and their use, for instance, are mentioned as a key part of the process, which involves issues of the subjectivity of viewpoints and experiences, the need to build a trusting relationship with the interviewee, or to take into account the context where the interview is carried out. As Catherine Guiral notes, one has to come to terms with “the intrusion of the everyday”, and learn to engage with it.

This account of working with history is refreshing in its down-to-earth attention to the actual conditions of research that, as every researcher knows, can look non-linear and erratic compared to the detailed research plans that are usually laid out at the start of academic projects. “Messy” research – a companion to Martha Scotford’s “messy history”2 – could be a useful and honest approach when investigating areas of design that are still to be studied and are not included in institutional archives and collections.

A key feature of this publication is the focus on how research, writing and design can contribute together to the production of compelling visual narratives. As Sara De Bondt notices, in books by designers-researchers “there’s liberty and closeness with the material, and there’s not this distance you sometimes get when a writer hands over the text and images to a designer or publisher. The form and content are more interconnected.” This is the case of books by Richard Hollis, Louise Sandhaus, Ellen Lupton and Abbott Miller, and Chris Lee, among others.

Graphic design history is usually meant for graphic designers, and it was initially developed with students in mind. To quote Alice Twemlow, “the design history that came out of this need was very instrumental in how it kind of created a lineage for these designers in training to insert themselves into”. But graphic design history can be also seen from other perspectives, as part of a wider visual culture that can attract the interest of non-specialized users. Catherine Guiral, discussing her research on Pierre Faucheux, points out how his work “was not just about graphic design. He was participating in another set of histories, including the history of French publishing, as he was also a small publisher […].”

Thanks to careful editing, the text flows effortlessly through a series of key issues such as archives and sources, historiography, publication, and documentation, exhibiting, using images, and so on.

The text is supported by many side notes providing quick biographical, bibliographical, and contextual information to complement the names and titles mentioned by the authors.

This editorial decision makes it clear that this publication is meant to reach a wide audience including professionals, researchers, and students. The choice of such a heavily discussed subject could have made it difficult to provide a new perspective on it, but this small publication manages to do more than simply summarizing the topic, by providing useful insights and a rich set of references.

Like the previous issues of Graphisme en France, Histoire(s) de design graphique was printed in 10000 copies and distributed to schools and design institutions; both the French edition and the English (Hi)stories of graphic design can be downloaded for free, as all the previous issues of the publication, on the Graphisme en France section of the CNAP website. This publication belongs to a broader series of projects launched by CNAP at the initiative of Véronique Marrier, such as the commission of two new typefaces, Infini by Sandrine Nugue (2014) and Faune by Alice Savoie (2018), both published under a Creative Commons license CC BY-ND 4.0.

…

1. Robin Kinross, “Conversation with Richard Hollis on Graphic Design History”, Journal of Design History 5, no. 1 (1992): 73–90.

2. Martha Scotford, “Messy History vs. Neat History: Toward an Expanded View of Women in Graphic Design”, Visible Languag, 28, no. 4 (1994): 368–388